Disorder vs the Human Condition

Mental health is an indispensable part of an individual’s well-being. It is the ability to fulfill one’s potential, cope with life’s stresses in a healthy manner, participate in society and benefit from community. According to the World Health Organization (WHO), mental health is a basic human right, crucial to personal, community and socio-economic conditions.

What is a mental health disorder?

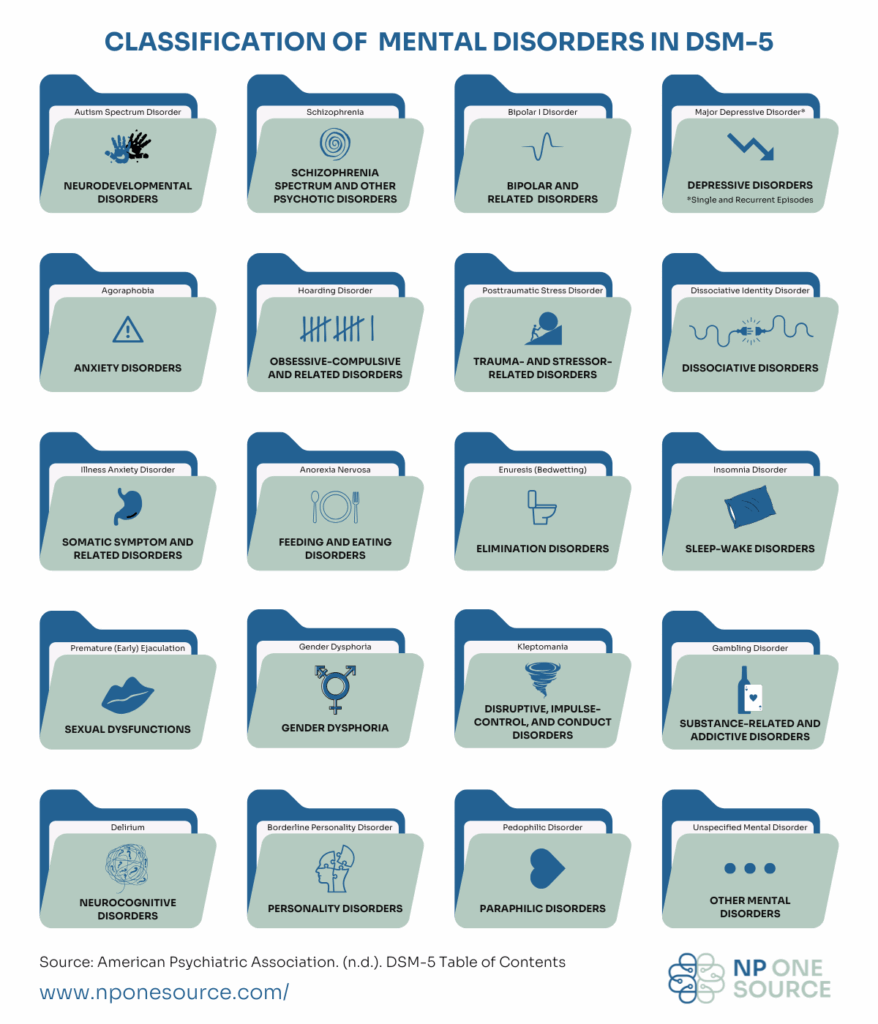

A mental health disorder is quite like its counterpart, a physical health disorder. It is a condition that interferes with systems that contribute to mental well-being. There are many different types of mental health disorders, outlined by the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, Fifth Edition (DSM-5). They are categorized by the functions they interfere with. Here’s a helpful infographic:

The DSM-5 is a diagnostic tool by the American Psychiatric Association. WHO annually develops a similar tool known as the International Classification of Diseases (ICD-11), now at their eleventh revision.

How does the DSM-5 help?

The DSM-5 is a guide that mental health professionals use to diagnose their patients, after identifying patterns of symptoms through medical examinations or psychometric testing. The diagnosis is used to identify the most effective treatment.

When symptoms aren’t causing interference in the patient’s life, neither a diagnosis nor treatment is needed. However, if the patient seeks the help of a professional for symptoms they’re struggling with (and a physical cause is ruled out), they are said to have mental health issues. If the issues persist despite treatment, the professional may look for repeated patterns and use that to diagnose the patient with a mental health disorder.

The purpose of a diagnosis is to improve the patient’s quality of life. It is not a label to be worn for the rest of their life. The patient is not the disorder. The patient’s actions and qualities cannot be predicted by their diagnosis.

What is a symptom?

A symptom is a sign of a condition that is perceived or experienced by the patient. While some symptoms may stand out as “out of the ordinary”, most symptoms are simply common human experiences that have become exaggerated or disruptive to the patient’s functioning. Let me illustrate this with an example.

During the pandemic, we collectively started washing our hands more frequently to prevent catching and spreading the coronavirus. For many, this habit could have even become a compulsion. They may not eat hand-held foods when there isn’t a sink nearby.

Now, imagine a patient who has been diagnosed with obsessive-compulsive disorder. One of their symptoms is germophobia, an extreme fear of catching and spreading germs. They may need to wash their hands an irrational number of times to feel safe from the germs.

Not having a sink nearby can cause them significant anxiety and even lead to a panic attack. They may regularly avoid new environments as they are unlikely to know whether there is a sink around or how clean the environment is. These behaviors can interfere with their mental health and quality of life, and can be considered symptoms.

This approach, which only uses a diagnosis to facilitate treatment, prevents patients from being labelled and discriminated against. It seeks to understand patients as products of their circumstances, and offer interventions that work for them rather than exclude them. After all, the subject of psychiatry and psychology is cut from the same cloth as the observer.